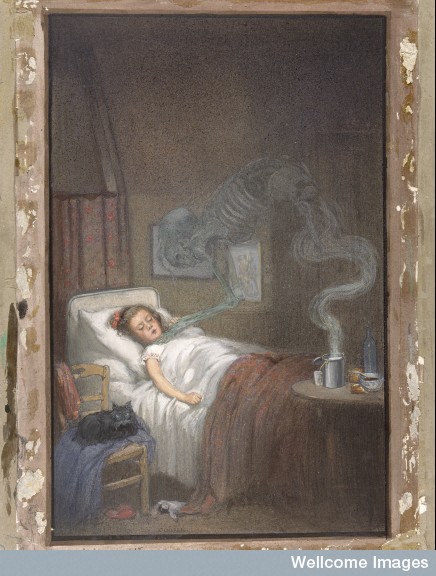

Diphtheria (Corynebacterium diphtheriae), an acute bacterial infection spread by personal contact, was the most feared of all childhood diseases. Diphtheria may be documented back to ancient Egypt and Greece, but severe recurring outbreaks begin only after 1700. One of every ten children infected died from this disease. Symptoms ranged from severe sore throat to suffocation due to a ‘false membrane’ covering the larynx. The disease primarily affected children under the age of 5. Until treatment became widely available in the 1920s, the public viewed this disease as a death sentence.

Diphtheria (Corynebacterium diphtheriae), an acute bacterial infection spread by personal contact, was the most feared of all childhood diseases. Diphtheria may be documented back to ancient Egypt and Greece, but severe recurring outbreaks begin only after 1700. One of every ten children infected died from this disease. Symptoms ranged from severe sore throat to suffocation due to a ‘false membrane’ covering the larynx. The disease primarily affected children under the age of 5. Until treatment became widely available in the 1920s, the public viewed this disease as a death sentence.

In the 1880s Dr. Joseph O’Dwyer, a Cleveland native, developed a method of intubating patients (inserting a tube to keep the airway open) to survive the life-threatening phase of diphtheria. Although neither foolproof nor simple to use, O’Dwyer’s intubation instruments comprised a life-saving last resort. Grateful patients, parents, and doctors acclaimed Dr. O’Dwyer, and hailed his instruments as modern medical marvels. Ironically, O’Dwyer lived long enough to see his invention eclipsed by progress in medical science. Diphtheria became a seldom-seen threat to children, but only so long as they had been vaccinated.

Before Dr. O’Dwyer perfected his intubation techniques, tracheotomy presented the only viable treatment for diphtheria. This procedure involved cutting open the throat without anesthetic and inserting a tube directly into the trachea. Through this tube, an attendant could maintain consistent airflow by pushing air into the lungs. Although tracheotomy has been practiced for hundreds of years, operative complications persisted until the 1960s. During the early 19th century tracheotomy remained a last resort due to the lack of anesthesia, high risk of infection, and low success rate of the procedure.

Before Dr. O’Dwyer perfected his intubation techniques, tracheotomy presented the only viable treatment for diphtheria. This procedure involved cutting open the throat without anesthetic and inserting a tube directly into the trachea. Through this tube, an attendant could maintain consistent airflow by pushing air into the lungs. Although tracheotomy has been practiced for hundreds of years, operative complications persisted until the 1960s. During the early 19th century tracheotomy remained a last resort due to the lack of anesthesia, high risk of infection, and low success rate of the procedure.

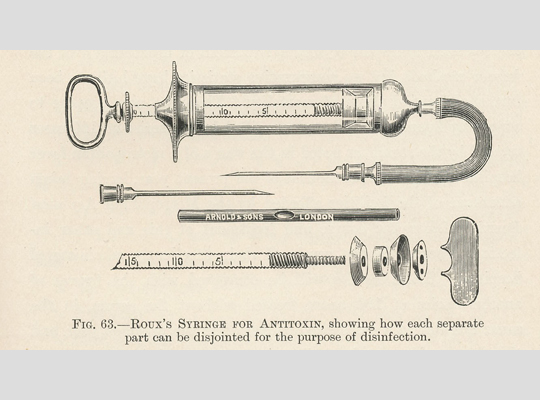

Diphtheria vaccination first appeared in the 1890s, but only became widely used in the 1920s. During this interval medical scientists labored to create a safe and effective vaccine. Antitoxin introduced in 1890 provided immunity for only two weeks. Six years later, the toxin-antitoxin mixture came into general use, providing life-long immunity. Doctors used horses to generate this antitoxin serum. Thirty years after diphtheria antitoxin first became available, Béla Schick introduced the Schick test, a cutaneous test showing if a person needed immunization. This allowed for the use of toxin-antitoxin to become widespread.

The toxin-antitoxin mixture, for all its promise, posed significant risks because it involved injecting live toxin. In 1924, Gaston Ramon developed the toxoid, a neutralized form of the toxin that would still impart permanent immunity. The toxoid-antitoxin mixtures eventually developed into the TDAP vaccine that is still in use today.

Cleveland did not escape the diphtheria outbreaks of the 19th century unscathed. In 1875, the 243-person death toll from diphtheria comprised 8.2% of all reported deaths. As was typical of the disease, children comprised most of the mortalities. Cleveland experienced  deadly waves of the disease until the late 1920s when immunization became standard practice in large parts of the city. By 1938, only a handful of cases were reported.

deadly waves of the disease until the late 1920s when immunization became standard practice in large parts of the city. By 1938, only a handful of cases were reported.

Balto is known worldwide as the dog from the Disney movie. This story is based on the real-life 1925 serum run to Nome, Alaska. In midwinter, news reached Anchorage of an imminent epidemic in Nome. Twenty mushers and more than 100 sled dogs relayed antitoxin through dangerous, freezing conditions in an effort to stave off the outbreak. The real Balto led the sled team that made the final leg of this dangerous journey. Balto, a neutered animal, could not be used for breeding and was soon disregarded. A Cleveland businessman found Balto and his team on display in Los Angeles and, outraged at the animals’ state of neglect, worked with the Plain Dealer to have the team brought to the Cleveland Zoo. Balto was taxidermied after his death and is now on display at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

Guest post based upon the Dittrick Museum Diphtheria Exhibit, guest curated by Cicely Schonberg, BS, from Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio.

Interested in learning more? Join us at the Dittrick Museum–researchers welcome!