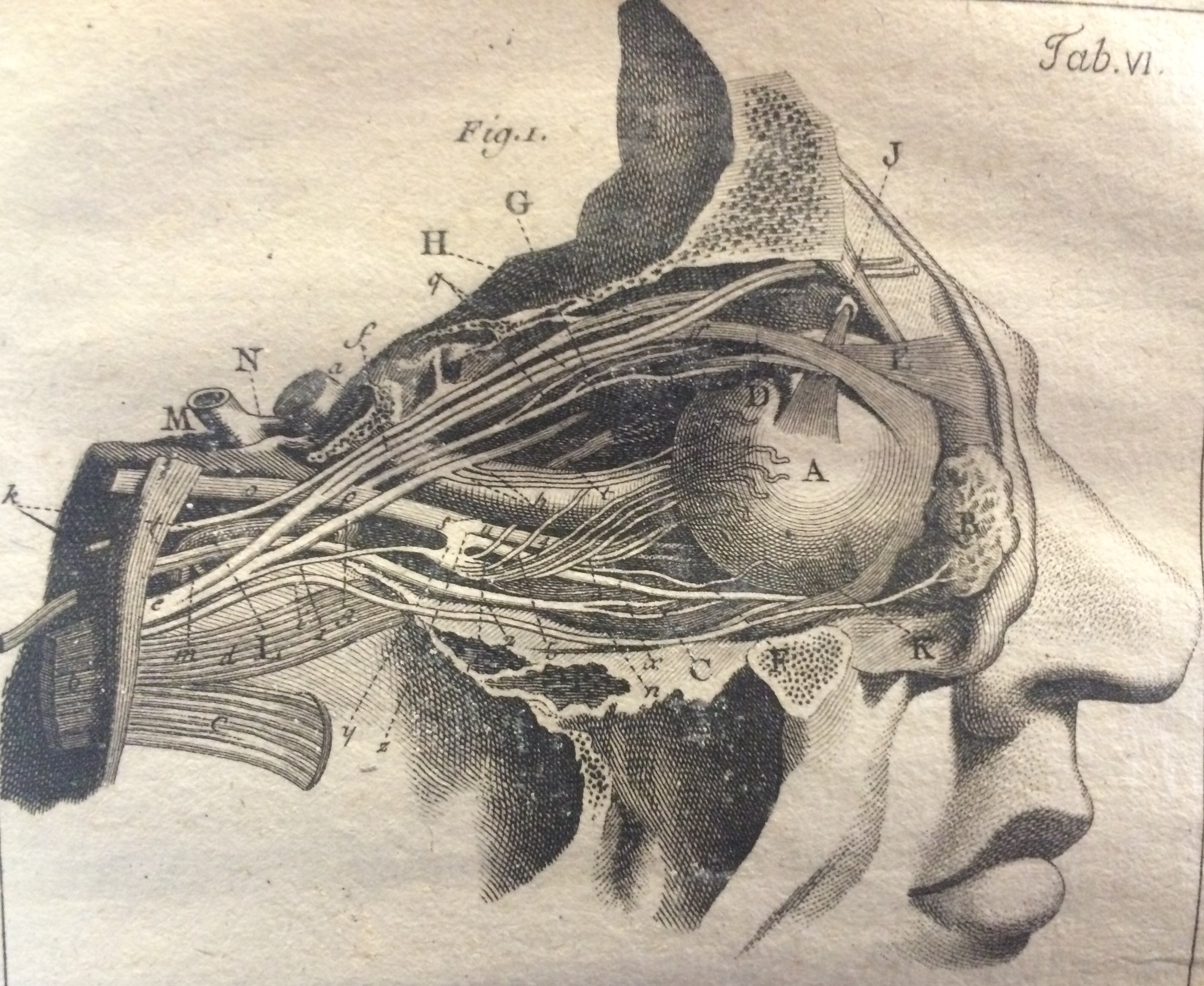

Fig. 1: Engraving of the eye in A Complete Physico-Medical and Churugical on the Human Eye and the Demonstration of Natural Vision (Degraver, 1780).

There is not one Part of the whole Body, that discovers more Art and Disign (sic), than this small Organ: All its Parts are so excellently well contrived, so elegantly formed and nicely adjusted that none can deny it to be an Organ as magnificent and curious, as the Sense is useful and entertaining.

— William Porterfield in A Treatise on the Eye, The Manner and Phaenomena of Vision, 1759

The Dittrick Museum is thrilled to have Dr. Jonathan Lass present “Eye of the Artist” for the upcoming Zverina Lecture on Oct. 14th. Dr. Lass, the Charles I. Thomas Professor, and formerly chair, in the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at Case Western Reserve University and Medical Director of the Cleveland Eye Bank, will discuss the ways eye conditions impacted the work of artists including Pissaro, Monet, Degas, and O’Keefe, and how individual vision could influence major artistic movements throughout history.

Although Dr. Lass will focus on pathological conditions for his lecture, today’s post looks at how 18th century physicians described “normal” or “natural” vision. These authors’ considered the eye, with its delicate structures and wondrous design, as a work of art. To disseminate research about these intricacies, engravers used immense skill and detail to produce anatomical representations (Fig. 1) and optics diagrams (Fig. 2).

Aside from graphical renditions, these early writings on the eye relied on artistic terms. Rays of light “paint” images onto the retina and these unique “strokes” are received by the Sensorium (the sensory part of the brain) and interpreted as “sketches of nature” by a viewer’s Mind.

Medical authors’ use of this artistic terminology reflected contemporary discussions surrounding the relationship between vision and reality. Were the perceptions of the Mind accurate depictions of the environment or were they truly only “sketches”? Could the eyes be trusted as empirical tools in science, or were external devices, like microscopes, necessary to ensure precise experimental data? Do eyes act as artists or instruments? Debates about the nature of colors (inherent in objects, dependent on light, created by the eyes) and the origins of delusions (originating from the mind or the organs) circled in scientific communities where the hallmark of research was eye-witnessed experimentation.

We hope you join us for the Zverina Lecture to hear more about how the eyes’ structure and function influence perceptions of reality, and how major artists’ health impacted the way they saw and portrayed the world around them.

The talk begins at 6:00PM, followed by a reception in the Dittrick Museum gallery. There is no charge, but you must register to get a seat! Please RSVP to Jennifer Nieves at 216/369-3648 or via email at jks4@case.edu

Sources:

Chandler, George. 1780. A treatise on the diseases of the eye and their remedies; to which is prefixed, the anatomy o the eye; the theory of vision, and several species of imperfect sight. London: T. Cadell in the Strand.

Degravers, Peter. 1780. A complete physico-medical and chirurgical treatise on the human eye: and a demonstration of natural vision. The whole illustrated with a variety of fine engravings, representing the anatomy of the eye, and instruments necessary for the chirurgical disorders. London: B. Law, Ave-Maria Lane.

Gataker, Thomas. 1761. An account of the structure of the eye, with occasional remarks on some disorders of that organ, delivered in lectures at the theatre of surgeons-hall. London: R. and J. Dodesly.

Porterfield, William. 1759. A treatise on the eye, the manner and phaenomena of vision. In two volumes. Edinburgh: G. Hamilton and J. Balfour.

Shapin, Steven and Simon Schaffer. 1985. The leviathan and the air-pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the experimental life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.