When Dutch spectacle-makers first crafted the microscope around 1600, they revealed a hidden world of tiny organisms! Who could imagine such monsters lived out of sight? But the early microscope only offered low magnification and blurry images; it would take improvements by Robert Hook to turn a novelty enjoyed for its curious revelations into a serious scientific tool.

When Dutch spectacle-makers first crafted the microscope around 1600, they revealed a hidden world of tiny organisms! Who could imagine such monsters lived out of sight? But the early microscope only offered low magnification and blurry images; it would take improvements by Robert Hook to turn a novelty enjoyed for its curious revelations into a serious scientific tool.

Who Was Robert Hooke?

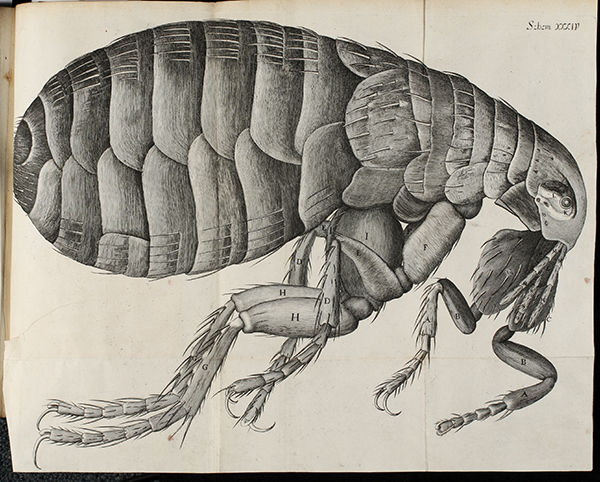

English philosopher Robert Hooke’ published Micrographia: in 1665 and brought microscopy into public view in sensational fashion. The profusely illustrated book ranged widely from the construction of microscopes themselves, to the spectrum of color, the crystal structure of objects, and the anatomy of insects. Here Hooke described and illustrated a thin cutting of cork that he said was “all perforated and porous, much like a Honey-comb.” Its porous structure reminded him of small monastic rooms, or cella (in Latin), so he called them “cells,” the basic unit of life. Despite some early observations of bacteria and cells, the microscope impacted other sciences, notably botany and zoology, more than medicine. Important technical improvements in the 1830s and later corrected poor optics, transforming the microscope into a powerful instrument for seeing disease-causing micro-organisms.

Lister and the Achromatic Microscope

In 1830 wine-merchant and amateur scientist Joseph Jackson Lister* introduced microscope lenses that eliminated blurring and color distortion afflicting higher power microscopes. Lister’s breakthrough, the ‘achromatic’ lens, transformed the microscope into a powerful tool capable of much higher magnification. It just so happens that the Dittrick has the same time of microscope on display! The enormous improvements converged with the emergence of bacteriology driven by the work of Pasteur and Koch, and by the 1880s, the microscope became an essential tool of doctors in the daily practice of identifying pathogens. This pioneering work allowed for easy identification of epidemic and endemic diseases; once doctors understood what caused illness, they could combat its spread through quarantine, disinfection, vaccines, and antibiotics. Public health was born!

In 1830 wine-merchant and amateur scientist Joseph Jackson Lister* introduced microscope lenses that eliminated blurring and color distortion afflicting higher power microscopes. Lister’s breakthrough, the ‘achromatic’ lens, transformed the microscope into a powerful tool capable of much higher magnification. It just so happens that the Dittrick has the same time of microscope on display! The enormous improvements converged with the emergence of bacteriology driven by the work of Pasteur and Koch, and by the 1880s, the microscope became an essential tool of doctors in the daily practice of identifying pathogens. This pioneering work allowed for easy identification of epidemic and endemic diseases; once doctors understood what caused illness, they could combat its spread through quarantine, disinfection, vaccines, and antibiotics. Public health was born!

The Cleveland Connection

Dudley Peter Allen (for whom the Allen Memorial Medical Library is named) acquired an Edmund Hartnack type of microscope (c1881) in Berlin during his medical ‘grand tour’ of Europe (1880-82). Allen learned first-hand of exciting advances in antiseptic surgery and the medical sciences, including landmark work in bacteriology by Robert Koch (who also owned a Hartnack microscope). Allen used this microscope to study prepared pathology specimens, particularly at the laboratory of Clemens von Kahlden, a pathologist and expert in microtechnique in Freiburg, Germany. Better yet, he traced the specimens and returned to Cleveland with full color notebooks illustrating various disease specimens, ranging from infectious diseases like tuberculosis to various neoplasms or cancers.

Dudley Peter Allen (for whom the Allen Memorial Medical Library is named) acquired an Edmund Hartnack type of microscope (c1881) in Berlin during his medical ‘grand tour’ of Europe (1880-82). Allen learned first-hand of exciting advances in antiseptic surgery and the medical sciences, including landmark work in bacteriology by Robert Koch (who also owned a Hartnack microscope). Allen used this microscope to study prepared pathology specimens, particularly at the laboratory of Clemens von Kahlden, a pathologist and expert in microtechnique in Freiburg, Germany. Better yet, he traced the specimens and returned to Cleveland with full color notebooks illustrating various disease specimens, ranging from infectious diseases like tuberculosis to various neoplasms or cancers.

Imagine a world where we could not identity disease-causing bacteria or cancerous cells? Pathology, bacteriology, even forensics and genetics, all owe a deep debt to the humble microscope. What began as a bead of glass for magnifying became the complex scopes that allow us to see even the smallest particles of our world!