Bodies--they have always been something of a problem. Even when in good working order, the body can be cumbersome, messy, demanding, and unpredictable. It runs down; it gets ill; it needs constant attention. Eventually, the body dies, but these adventures are far from over. Where do you put a dead body? Burial arose in part to combat the spread of disease, but death rituals vary with climate and geography. You can't bury your dead in the frozen ground of Tibet, nor can you build a pyre where no trees grow for use as fuel. How we deal with bodies...

Medical History

Welcome back to the Dittrick Museum Blog!

This month, the Wellcome Collection's Object of the Month is celebrating a mainstay of health museums world-wide: the transparent anatomical model. In the write up, which explores the marred past of these devices in the war and post-war period--"a past that very few know about, a past that tells a story of redemption and new beginnings."

In the 1920s, the Deutsches-Hygiene-Museum in Dresden, Germany, created a fully operable model of the human body, depicting “the human body as a machine.” A transparent female form was made to join him. Despite becoming part of...

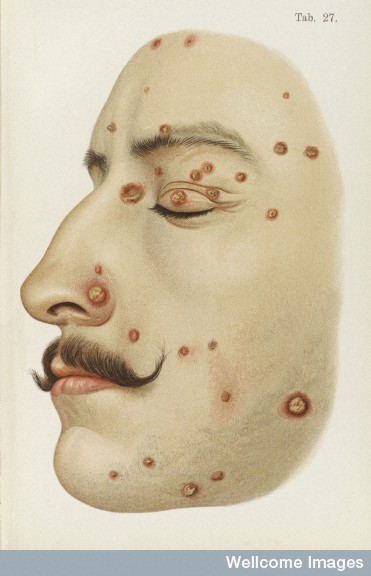

Syphilis. The word conjures the worst of fears--along with a set of relatively unpleasant images! Caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum, syphilis has four stages:

primary (wherein a single sore, or chancre, appears),

secondary (characterized by skin rash and lesions of mucous membranes),

latent stage (when symptoms disappear) and

late stage (wherein the disease attacks the nervous system and internal organs).

It affected the hair and nails, mucous membranes, tongue, larynx, abdomen, arteries, muscles, eyes and ears, nerves and--of course--the brain. Syphilis was dangerous in part because it could go "underground" in a sense, and people who looked perfectly healthy might yet have the...

In the spring, we ran a series of posts on Dr. William Smellie's "birthing machine," the obstetrical manikin he built to train man-midwives in the 18th century. The bizarre history of this--now vanished--device has always captivated me. How did it work? Where did it go?

And why was it called a "machine" at all?

William Smellie called the device a machine, possibly because mechanical automations of various sorts gained popularity in the eighteenth century. It was a way to set aside his "instrumental" engineering from the manikins of other teachers (including those used by women midwives). What on earth would that...