Anthony Comstock was born in 1844 in New Canaan, Connecticut. His father was a prosperous farmer, and his mother was a devout Congregationalist. She died when Comstock was only 10 years old, but her religious fervor remained alive in her son who clung to the “austere, fire-and-brimstone faith of his childhood.” Based on a firm belief that the devil’s temptations were omniscient, Comstock rationalized that abstinence from all impure thoughts and behaviors secured the faithful path to righteousness.

As a Union soldier in the Civil War, Comstock was stationed in a relatively peaceful area of Florida, removed from the glory of the “good fight”. He launched private battles against the use of tobacco, alcohol, gambling, and atheism among the armed forces through active participation in the Christian Commission. The Christian Commission, created by the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) to send ministers to Civil War battlefields, sought to enlist the power of the government in the effort to keep the soldiers moral. Aware that publishers were making obscene books and pictures available to soldiers, the Commission prompted a provision in the 1865 post office bill making it a misdemeanor to send “any obscene book, pamphlet, picture, print, or other publication of vulgar and indecent character” through the mails.

After his time in the Army, Comstock moved to New York City in search of his fortune. He was unprepared to face the hub of America’s commercialized sex industry. Prostitutes, pornographic materials, and erotica circulated freely around the city along with abortion services and contraceptives. In 1868, a close friend of Comstock’s was led down the path of moral decay by reading obscene materials. Comstock went on the offensive and with the help of the YMCA he began vice hunting. Learning of the 1865 obscenity law, Comstock took action against the offending book dealer. He bought an erotic book as evidence and then accompanied by the police captain of the precinct, had the bookseller arrested and his stock of books seized. In 1872 Comstock’s activities were brought to the attention of a founding member of the YMCA, who in turn introduced Comstock to other wealthy gentleman interested in reform. They gave Comstock’s efforts financial backing and organized the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV). The NYSSV was supported by some of the country’s wealthiest men in the City, but it was Comstock, employed full-time as the N YSSV’s agent, who brought the organization’s activities to the attention of the public.

The Comstock Act

As enacted , March 2, 1873, the Comstock law forbade the sending through the sending through the mails of any drug or medicine or any article whatever for the prevention of conception.” The 1873 act did not focus on fertility control, but was a statute that included birth control and abortion among a long list of commercial obscenities. Comstock rallied against contraceptive devices bought and sold in commercial spaces, not against natural forms of birth control such as abstinence and the rhythm method used privately at home. In making this distinction, he articulated the views of many Victorians who publicly supported family limitation only when it was achieved by dignified, “ethical” means. What Comstock found so objectionable was the prominence of contraceptives in the vice trade.

As enacted , March 2, 1873, the Comstock law forbade the sending through the sending through the mails of any drug or medicine or any article whatever for the prevention of conception.” The 1873 act did not focus on fertility control, but was a statute that included birth control and abortion among a long list of commercial obscenities. Comstock rallied against contraceptive devices bought and sold in commercial spaces, not against natural forms of birth control such as abstinence and the rhythm method used privately at home. In making this distinction, he articulated the views of many Victorians who publicly supported family limitation only when it was achieved by dignified, “ethical” means. What Comstock found so objectionable was the prominence of contraceptives in the vice trade.

The Comstock Act was amended in 1876 to read “Every obscene, lewd, or lascivious book, pamphlet, picture, paper, writing, print or other publication of an indecent character, and every article or thing designed or intended for the prevention of conception or procuring of abortion, and every article or thing intended or adapted for any indecent or immoral use, and every written or printed card, circular, book, pamphlet, advertisement, or notice of any kind giving information, directly or indirectly, where, or how, or of whom, or by what means, any of the hereinbefore mentioned matters, articles, or things may be obtained or made, and every letter upon the envelope of which, or postal card upon which, indecent, lewd, obscene, or lascivious delineations, epithets, terms, or language may be written or printed, are hereby declared to be non-mailable matter, and shall not be conveyed in the mails, nor delivered from any post-office, nor by any letter-carrier.”

Opponents to the law objected to the heavy handed and deceptive methods used by Comstock. He requested material under the guise of a distraught husband and when the material was provided he had the provider arrested. Comstock defended himself by saying “Not one of my opponents has ever been near me, or made a single inquiry at my office for facts. Without at least an attempt to get at the facts, they are not qualified to speak, and what they say should be viewed with suspicion and weighed with great care by thinking men. Thus is defined the true position of the opponents to the above law”.

Books by Comstock

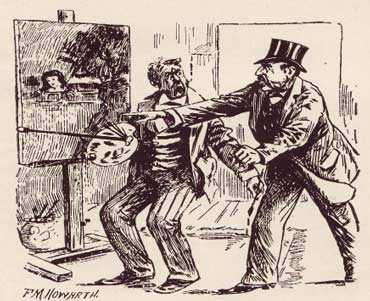

Life, 1888 “That Fertile Imagination”

Comstock is shown arresting an artist for depicting a woman

almost totally submerged. “Don’t you suppose I can imagine what is under the water?”

In Frauds Exposed (1872), Comstock expressed concern over the general health of society and condemned those who preyed on the sick, offering their concoctions in the press. The “quackery” market was flooded with self-help devices and medicines. Laymen, as well as physicians, could buy electrotherapy devices through catalogs. Tonics and pills compounded in backyards and basements were sold to people desperate for relief from illness. This easy availability concerned Comstock deeply. The plight of young people worried him especially. The quack “by his lying advertisements and worthless nostrums, traversing the …newspapers and mails…comes upon the suffering and afflicted ones, not only to deceive and heartlessly rob them, but to add to their suffering”.

In his second book, Traps for the young (1883), Comstock addresses parents, teachers and ministers, warning them of the peril to adolescent morals in dime novels, advertising and blatantly obscene literature. “The message of these evil things is death – socially, morally, physically and spiritually.”

Comstock’s last stand

Advocates of contraception had always evoked Comstock’s wrath. Their numbers increased dramatically, and Comstock felt the activists became more brazen through the years. Margaret Sanger’s pamphlet, Family Limitation, aroused his horror. Sanger, a visiting nurse who worked with New York City’s poorest women, was deeply effected by the plight of women who, when faced with another unwanted pregnancy, resorted to back-alley abortions. Comstock arrested Sanger’s husband, Bill Sanger, in January 1915 for distributing Family Limitation. This was to be Comstock’s last court case. Justice McInerney, at the September trial, said “In my opinion, this book is contrary not only to the law of the State, but to the law of God… If some of these women who go around advocating Woman Suffrage would go around and advocate women having children, they would be rendering society a greater service.” Bill Sanger was convicted and spent 30 days in jail. Comstock died on September 21, 1915, perhaps content in the knowledge that justice still prevailed.