The recent outbreak of measles at Disneyland has spurred a rash of competing newscast, blog posts, and social media responses. One question continues to be foremost–as quoted by CNN correspondent Mariano Castillo, “how bad is it?” Castillo reminds the reader: “to call the news surrounding vaccinations a “debate” is misleading. The scientific and medical consensus is clear: Vaccinations are safe, and they work.” [1] The question is not about efficacy but about consequences; parents may have a variety of reasons for not vaccinating their children, sometimes on the grounds of safety or mistrust of the vaccine. However, as pointed out by members of the CDC and others, those who do not vaccinate live in the same communities as those who do; what happens if measles once more establishes a foothold? What might be at stake? History can provide useful parallels–especially the history of how vaccines were first administered and why.

Deadly Childhood Diseases

I n 1875, the 243-person death toll from diphtheria comprised 8.2% of all reported deaths. As was typical of the disease, children comprised most of the mortalities. In the 1880s Dr. Joseph O’Dwyer, a Cleveland Ohio native, developed a method of intubating patients (inserting a tube to keep the airway open) to survive the life-threatening phase of diphtheria. Otherwise, the diphtheria infection slowly closed the throat, and children suffocated to death. [Dittrick Museum, hall exhibit. Read more.]

n 1875, the 243-person death toll from diphtheria comprised 8.2% of all reported deaths. As was typical of the disease, children comprised most of the mortalities. In the 1880s Dr. Joseph O’Dwyer, a Cleveland Ohio native, developed a method of intubating patients (inserting a tube to keep the airway open) to survive the life-threatening phase of diphtheria. Otherwise, the diphtheria infection slowly closed the throat, and children suffocated to death. [Dittrick Museum, hall exhibit. Read more.]

In 1898, Cleveland witnessed a minor outbreak of of the worlds most dreaded diseases: smallpox. Only a year later, the cases jump from 70 to 475, six times the rate of outbreak. In 1900, the numbers double again to 993–and then, in the pla gue years of 1901 and 1902, more than 1200 people become ill, with over 200 dying at the height of the disaster. Many of these were children. Those who survived the epidemic were left with horrendous scarring, the “pocks” that welted on the skin left their mark for a lifetime. [Dittrick museum, hall exhibit. Read more.]

gue years of 1901 and 1902, more than 1200 people become ill, with over 200 dying at the height of the disaster. Many of these were children. Those who survived the epidemic were left with horrendous scarring, the “pocks” that welted on the skin left their mark for a lifetime. [Dittrick museum, hall exhibit. Read more.]

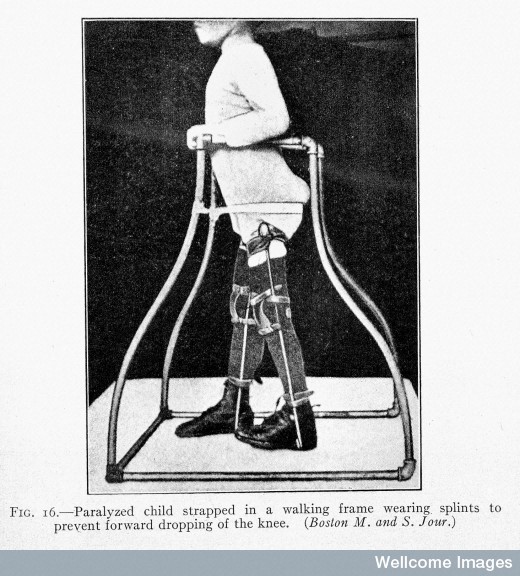

In the 20th century, one of the most feared childhood disorders not only killed, but crippled. Poliomyelitis killed more than 6000 people in the US in 1916 [2]; most were under the age of 14. Parents lived in fear; no one–not even President FDR–was safe. An early attempt at vaccine creation proved unsuccessful, and the disease continued. By 1952, 57,628 polio cases were reported in the United States, 21,000 of them paralytic cases.[2]

In each o f these epidemics, the victims were largely children–but also those with weakened immune systems, the elderly, the ill. The diseases attacked the powerless, who expired or were crippled under the horrifies gaze of their loved ones. And for much of history, no cure availed itself. But cures did come, in the form of vaccines. And strangely, the key to polio had been found be a man searching in desperation for a cure for measles.

f these epidemics, the victims were largely children–but also those with weakened immune systems, the elderly, the ill. The diseases attacked the powerless, who expired or were crippled under the horrifies gaze of their loved ones. And for much of history, no cure availed itself. But cures did come, in the form of vaccines. And strangely, the key to polio had been found be a man searching in desperation for a cure for measles.

Measles and Milestones

Measles does not, perhaps, sound as terrifying as small pox and polio. However, this highly contagious disease had a much higher mortality rate. Affected children were contagious both before and after the appearance of measles, and worse–it could survive in the air for over an hour just waiting for the next victim. [3] Children got diarrhea and vomited, had a vivid red rash and watery eyes. It hospitalized an average of 48,000 Americans each year through the 1960s, leaving the survivors compromised sometimes with brain damage or deafness. With over 4000 cases of encephalitis, many children became wards of the state. [2] In other, poorer, countries, millions died every year. Alexander Langmuir, chief CDC epidemiologist in 1961, stated emphatically: “Any parent who has seen his small child suffer even for a few days with a persistent fever of 105, hacking cough and delirium, wants to see this disease prevented.” [3]

At the same time, it was important for Langmuir that the vaccines be safe. In 1935, Maurice Brodie and John Kolmer tested a polio vaccine that proved disastrous and even deadly. It would be 1952 before the next serious trial, the successful Salk and Sabine vaccines. John Enders, who found the key to polio while looking for a measles cure, created a vaccine of mild measles that was added to other boosters children received for the diseases mentioned above. At last, children could be better protected and parents need not fear the daycare centers or play dates, school yards or other common grounds that had harbored these diseases. [3]

That does not mean, of course, that vaccines were unproblematic. The first disease to yield a vaccine was, in fact, smallpox. Edward Jenner injected a milder version, that of cowpox, into a healthy child. The act of risk and daring would be considered highly unethical today–but again, small pox killed and maimed many in the 18th century. The treatment worked. For polio, the earlier trial had resulted in illness and death. A later version, by Albert Sabin, introduced a weakened but still living virus. Jonas Salk’s vaccine worked by stimulating the immune system against polio without giving a live virus. Complications still arose, such as the contamination of both vaccines with SV40 virus at a facility of American Home Products. Even so, the US was polio free by 1979, and the crippling, painful, deadly disease no longer threatened American children. Measles, mumps, rubella, smallpox, polio, and diphtheria–despite setbacks, US parents, spurred by public action and social responsibility as well as the need to protect their own children, flocked to immunization centers. The understanding: we aren’t protected until we are *all* protected.

But the truth is, these diseases have not vanished. They rage in other countries and among the poor and disenfranchised. Viruses are no respecter of persons or of borders, and in this global world, they come unbidden. The World Health Organization recently published some facts about measles, alone:

- Measles is one of the leading causes of death among young children even though a safe and cost-effective vaccine is available.

- In 2013, there were 145 700 measles deaths globally – about 400 deaths every day or 16 deaths every hour.

- Measles vaccination resulted in a 75% drop in measles deaths between 2000 and 2013 worldwide.

- In 2013, about 84% of the world’s children received one dose of measles vaccine by their first birthday through routine health services – up from 73% in 2000.

- During 2000-2013, measles vaccination prevented an estimated 15.6 million deaths making measles vaccine one of the best buys in public health.[4]

The outbreak in Disneyland does not represent a strange isolated event, but a reintroduction of a dangerous virus onto American soil. The history of vaccination does not suggest that the process or practice was easier then than now; quite the reverse. But the impetus to immunize was driven far less by an understanding of choice and far more by a unified desire to eradicate disease…and by the still-painful and still-present memories of its horrors.

References

[1] Mariano Castillo. “Measles Outbreak: How bad is it?” CNN Feb 2, 2015 http://www.cnn.com/2015/02/02/health/measles-how-bad-can-it-be/ [2] Polio Timeline, History of Vaccines http://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/timelines/polio [3] Arthur Allen. Vaccine: The Controversial Story of Medicine’s Greatest Lifesaver. London, Norton 2007 (216-217) [4] Measles. World Health Organization. Nov 2104. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs286/en/Additional reading:

Lucas, William Palmer, 1880-1961. Experiments as to the protective value of certain specific sera and vaccines against the virus of poliomyelitis / by William P. Lucas and Robert B. Osgood. Boston, Mass. : Wright & Potter Printing Co., State Printers … , 1912

Horder, Thomas J. (Thomas Jeeves), 1871-1955. Clinical pathology in practice, with a short account of vaccine-therapy, by Thomas J. Horder ..London, H. Frowde; Hodder & Stoughton, 1910

Kirkpatrick, J. (James), approximately 1696-1770. The analysis of inoculation: comprising the history, theory, and practice of it: with an occasional consideration of the most remarkable appearances in the small pocks. London, J. Buckland [etc.] 1761

Author: Brandy L Schillace, PhD, Research Associate/Guest Curator, Dittrick Medical History Center