Welcome back to the Dittrick Museum Blog!

Welcome back to the Dittrick Museum Blog!

Today, we are pleased to host guest-blogger Cali Buckley, Ph.D. Candidate in Art History, Pennsylvania State University. Cali has been doing some fascinating research on ivory anatomical models, three of which reside in the Dittrick Collection. Delicate, finely carved, and impossibly detailed, these ivory anatomical models are both fascinating and mysterious. Today, Cali will be talking to us about their curious and often uncertain past. We hope you will join us at the Dittrick Museum’s history of birth exhibit, and take a closer look for yourself!

The Elusive Past of Ivory Anatomical Models

Cali Buckley, Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Art History, Penn State University

[all images reproduced by permission of Dittrick Medical History Center, Case Western Reserve University]

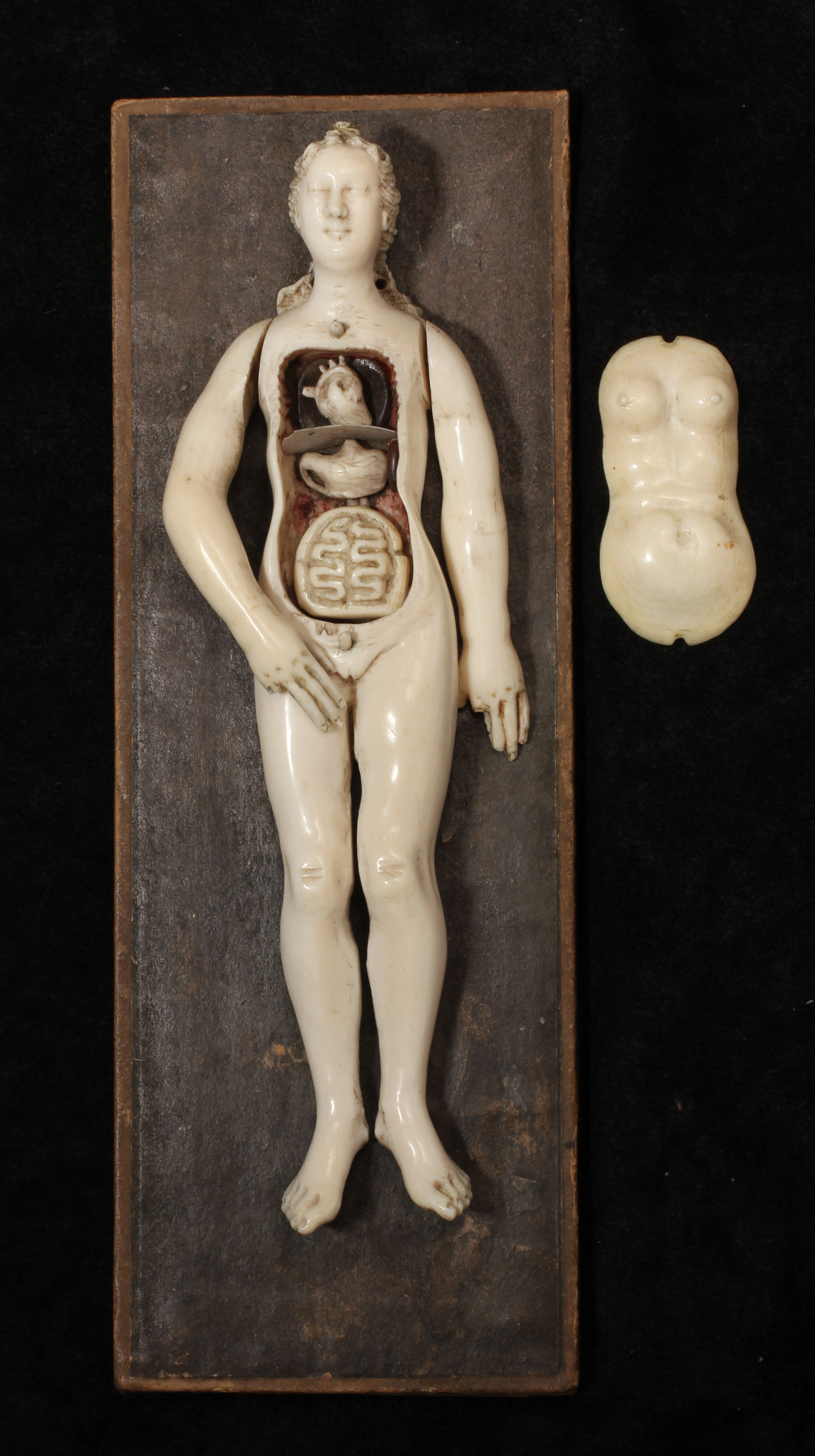

The Dittrick Museum is ready to show some of the most curious and least understood objects in the history of medicine: ivory anatomical manikins. They are hand-carved and highly intricate but rarely longer than a man’s hand. Nonetheless, when the top of the body is opened, they reveal a number of minuscule ivory organs. A majority of these models have articulated arms and—for the large percentage which are female—a tiny fetus attached to his mother by a red umbilical string. There are a little over 100 of these manikins known today in collections spanning Europe and the United States, but the question remains: What were they used for?

What we do know is that most of them were probably produced in Germany and owned by male physicians. The first manikins were pioneered by the ivory carver Stephan Zick (1639–1715) of Nuremberg, who also made ivory models of the eyes and ears.[1] Often the models passed from one doctor’s hands to another’s, such as those at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Huntington Library in San Marino, California.[2] Ignaz Semmelweis—who nearly eradicated puerperal fever in new mothers of the mid-nineteenth century by insisting that male ‘midwives’ wash their hands—also had a manikin, now in a museum in Budapest named for him.[3] By the 1930s the market was saturated such objects to the point that the buyers for the Wellcome Collection would not acquire any single pieces above ten pounds sterling.[4] Unfortunately, many of the sellers of these objects were killed in concentration camps, and their collections dispersed during World War II.

There are at least a few bits of text that can give us more insight into how these manikins were used. In 2007 a manikin owned by the famous French obstetrician Francois Mauriceau (1637–1709) was sold by Christie’s auction house. It bore a curious inscription transcribed by the sellers as “Bon den ßufallen ß krantheiten der Sibivangern ßeiber ud kindbetterinnen.”[5] A rendering of it into modern German might read as “von den zufallen der krankheiten der schwangeren Weiber und Kindbetterinnen” or “for the diseases befalling pregnant women and those who have just given birth.”[6].

These ivory models were once thought to have been used as tools for doctors to explain childbirth to expectant mothers, but given the evidence we do have, this scenario is unlikely.[7] The Wellcome Collection acquired a poem with one of its manikins. It was signed by the Italian obstetrician Juseph Fuardi de Fossau in 1786. The original French has been translated as:

In Life’s full bloom, when labour’s toil so near My fellow sufferers’ lot and perils I do fear, Come ye fair pupils, Lo, I cast aside my shame That Midwif’ries secrets may reveal my frame. Pierce it with keen enquiring eye, and may The child and mother’s nature then convey New manifold devices to your skillful art That pining women may not henceforth smart Through cruel untaught efforts, and not gasp With their unborn in Death’s unpitying grasp.[8]

Fuardi points to medical students as the manikins’ primary audience while advertising and vindicating the trained physician’s role in the birthing process. He also echoes the sentiments put forth by doctors when they first began to offer their own insights into women’s medicine starting with Eucharius Rösslin in sixteenth-century Germany.

The manikins themselves can hardly be considered pragmatic given that their pieces seem to be caricatures of actual body parts and they are so small that they can barely convey any information. They were after the printed “flap anatomies” made for wide audiences to see inside the body and the much more accurate wax Venuses of Florence and Vienna. As ivories, these manikins catered to trained medics who collected ivory instruments of various sorts from models to instruments such as enema syringes and scalpel or saw handles. The material was also a signifier of wealth. Though these tiny women were not highly functional in a physical sense, they were part of a wunderkammer mentality whereby objects become symbols of the curiosities of the universe—in addition to acting as a display and preservation of affluence.

Though it is nearly impossible at this time to attribute specific manikins to their makers, they do fall into stylistic groups. The manikin on a red velveteen bed may be related to other models in the Istituto Ortopedico Rizzoli in Bologna,[9] the Victoria and Albert Museum in London,[10] and five examples owned by the Wellcome Collection in London. Another is very similar to another in the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig,[11] one in the Olbricht Collection, Essen,[12] and two in the Wellcome Collection. The supine woman on the faded and elevated platform is

Though it is nearly impossible at this time to attribute specific manikins to their makers, they do fall into stylistic groups. The manikin on a red velveteen bed may be related to other models in the Istituto Ortopedico Rizzoli in Bologna,[9] the Victoria and Albert Museum in London,[10] and five examples owned by the Wellcome Collection in London. Another is very similar to another in the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig,[11] one in the Olbricht Collection, Essen,[12] and two in the Wellcome Collection. The supine woman on the faded and elevated platform is  unique. There are a number of manikins that seem to be one-offs, and they likely originated from an artisan attempting to copy the format, but it is also possible that a great number of other ivory figurines were lost or destroyed due to breakage, lost parts, and their unfortunate labeling as ‘novelties’.

unique. There are a number of manikins that seem to be one-offs, and they likely originated from an artisan attempting to copy the format, but it is also possible that a great number of other ivory figurines were lost or destroyed due to breakage, lost parts, and their unfortunate labeling as ‘novelties’.

These manikins may not be scientifically useful, but their making was such that they performed as pieces to distinguish the male doctor as someone who was focusing on women’s medicine and was willing to purchase or commission an object dedicated to his work. Having been made in Germany at a time when men were still attempting to prove their usefulness in terms of childbirth and the education of midwives, such objects take on a new light, offering a means for male doctors to convey what they did know about the female body. Whether lying silently in their private vitrines and cases or being ‘performed upon’ by a doctor for the eyes of curious students, these ivory ladies were instruments of a different kind.

[1] Eugene von Philippovich, Elfenbein (Munich: Klinkhardt und Biermann, 1981), 331.

[2] Information from Marjorie Trusted, The Victoria and Albert Museum. The Huntington’s manikin was owned by a Dr. Edward Bodman. I thank Dan Lewis at the Huntington Library for this information.

[3] Ákos Palla, István Örkény, Miklós Pap, László Székely, Lajos Vörösházy, ed., Nymphis Medicis (Budapest: Kossuth Press, 1962), cat. 62.

[4] This information was gleaned from the correspondence at the archives of the Wellcome Collection, London.

[5] “An Ivory Anatomical Figure of a Woman,” Sotheby’s website, Lot 62, London, December 5, 2007: http://www.sothebys.com/en/catalogues/ecatalogue.html/2007/european-sculpture-and-works-of-art-l07233#/r=/en/ecat.fhtml.L07233.html+r.m=/en/ecat.lot.L07233.html/62/

[6] This was sold to an anonymous bidder and the original text is no longer available.

[7] Le Roy Crummer, “Visceral Manikins in Carved Ivory,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 13 (1927): 29.

[8] The original text is now lost. Translated in C. J. S. Thompson, “Anatomical Manikins,” Journal of Anatomy 59.4 (July, 1925): 442–447.

[9] Roberto Margotta, Medicina nei secoli (Milan: Mondadori Editore, 1967), 187.

[10] Information from Marjorie Trusted, The Victoria and Albert Museum.

[11] http://kulturerbe.niedersachsen.de/viewer/image/isil_DE-MUS-026819_opal_herzanulm_kunshe_Elf186/1/

[12] Hiltrud Westermann-Angerhausen and Andrea von Hülsen-Esch, Zum Sterben schön: Alter, totentanz und sterbekunst von 1500 bis heute (Schnell und Steiner, 2006), 143.

______________________________

ABOUT THE BLOGGER

Cali Buckley is a Ph.D. Candidate in Art History at Penn State University. She is currently working on a dissertation entitled “Women of Substance: The Materiality of Anatomical Models and the Control of Women’s Medicine in Early Modern Europe.” She has examined over 75 ivory manikins across the world and is compiling a catalogue of them so that museum curators, librarians, collectors, and scholars can learn more about these objects.