In the early part of the 19th century, a fine, white powder was all the rage among murderers (and some would-be beneficiaries). It was easy to acquire and easy to administer, too. Tasteless and colorless, it might be added to food or water and ingested. It was even called the “inheritor’s powder” because it aided in the rapid passing of the rich and elderly.

In the early part of the 19th century, a fine, white powder was all the rage among murderers (and some would-be beneficiaries). It was easy to acquire and easy to administer, too. Tasteless and colorless, it might be added to food or water and ingested. It was even called the “inheritor’s powder” because it aided in the rapid passing of the rich and elderly.

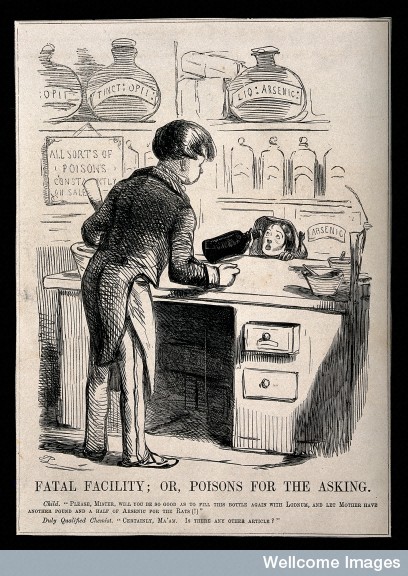

What was arsenic doing on shelves to be purchased, you might ask? In the 19th century, arsenic was used in wallpaper, beer, wine, sweets, painted toys, insecticides, clothing, hat ornaments, coal, and candles (A further list of uses may be found in James C. Whorton’s The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain Was Poisoned at Home, Work, and Play). But of course, arsenic is still used today, frequently an  ingredient in ant poison and insecticides; Michael Swango, a 20th century Dr. Death, used arsenic to sicken his colleagues before going on to kill his patients with other drugs. Swango got caught–but early 19th century poisoners did not. Why?

ingredient in ant poison and insecticides; Michael Swango, a 20th century Dr. Death, used arsenic to sicken his colleagues before going on to kill his patients with other drugs. Swango got caught–but early 19th century poisoners did not. Why?

As usual, the devil’s in the details. The 19th century might have been subject to a plague of poisonings, but it had other plagues, too. Cholera, for instance, was a frequent cause of death. Cholera affects the small intestine, and the more common signs are diarrhea and vomiting… which are also the signs of arsenic poisoning. In 1831, an outbreak in the UK claimed 52,000 lives. Who would notice a few poisonings in the midst of all that?

Well, in turns out someone would. His name was James Marsh. A chemist, Marsh was brought in for the sensational case of George Bodle’s death, wherein an entire family and servants fell ill (though only the patriarch died) in 1833. The test that March developed was complex, but he had found that adding bodily tissues to a glass vessel with zinc would produce a gas; if heated and ignited, it would turn to arsenic and water vapor (which would be seen as a metallic film on a ceramic vessel). Earlier discoveries has been made by Carl Wilhelm Scheele and Johann Metzger, but Marsh’s was the first time the body itself could yield solid clues.

The Marsh test was taken further yet by a French case, the poisoning of Charles Lafarge. Marie Lafarge was charged with the murder and the trial polarized French society. Botched Marsh experiments nearly saw her go free, until toxicologist Mathieu Orfila–and his extraordinarily methodical and scientific methods–proved beyond doubt that the she had murdered her husband.

By the end of the 19th century and into the 20th, arsenic lost favor. It had become too easy for forensic toxicologists to find it. In 1880, Edward Salisbury Dana’s Microscopic examination of samples of commercial arsenic, and the practical results to which it leads was published in New Jersey. Here in Cleveland, as part of the Western Reserve medical school in 1882, Oliver Franklyn Gordon even wrote his final thesis on arsenic, adding to a large and increasing literature on the subject. That doesn’t mean arsenic fell out of favor in general, however; Salvarsan 606, used to treat syphilis, was an arsenic compound–and of course, it’s still the bane of the invasive and unwanted ant colony.

Forensic science had a long history before CSI and other detective shows made it popularly regarded. Here at the Dittrick, we hope to explore more of this rich history for a spring exhibit: Steampunk, Sherlock, and Forensics. We will be posting additional details as soon as they become available; look for more in March!