Given that it is Valentine’s Day, we are taking a short break from our series on forensics and poisoning. (Granted, a number of those poisonings were, themselves, “affairs of the heart!”) Today, we celebrate the history of cardiac care, and of Cleveland, where so many of those innovations began.

Given that it is Valentine’s Day, we are taking a short break from our series on forensics and poisoning. (Granted, a number of those poisonings were, themselves, “affairs of the heart!”) Today, we celebrate the history of cardiac care, and of Cleveland, where so many of those innovations began.

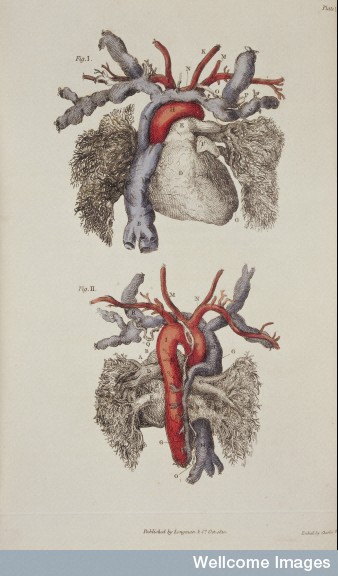

In the 1930s, Western Reserve surgeon Claude Beck perfected operations to improve heart circulation. That might not seem like a feat, but when you understand the circumstances, it becomes a matter of life and death.

When Beck performed cardiac surgery, the heart sometimes went into ventricular fibrillation–in other words, heart muscles twitched and contracted rapidly, disrupting the normal rhythmic heartbeat, a life-threatening condition. Beck could massage the heart, but this did not always stop the fibrillation and the patient would die on the operating table! Beck became desperate for a remedy, and he learned that a colleague at Western Reserve, the physiologist Carl J. Wiggers, had maintained  circulation in laboratory animals by manual massage of the heart, followed by electrical defibrillation. Beck concluded that using electric shock to counteract fibrillation and restore normal heart rhythm would work for humans, too. It was risky, but then, the heart surgery itself was risky–he was willing to do anything to save his patients.

circulation in laboratory animals by manual massage of the heart, followed by electrical defibrillation. Beck concluded that using electric shock to counteract fibrillation and restore normal heart rhythm would work for humans, too. It was risky, but then, the heart surgery itself was risky–he was willing to do anything to save his patients.

In 1947, Beck had his chance. He successfully revived a patient for the first time during an operation, the fibrillation ceased and normal heart beat was restored! Subsequently, patients were resuscitated outside the operating room as well–though it still required the chest to be opened. One operation actually occurred on the hospital steps!

Finally, massage and defibrillation across the intact chest made cardiac resuscitation available at any place or time. Defibrillators have since been used daily in hospital emergency rooms and EMS units across the country. Almost everyone knows what it means when someone shouts “Clear!” and tiny defibrillators can be inserted right into the chest cavity (my father, for instance, has one of these.)

Beck and his colleagues also developed cardiopulmonary resuscitation techniques (CPR), and with the help of the Cleveland Heart Society, they trained more than 3,000 doctors and nurses in 20 years. By 1963, they added a course in closed-chest cardiopulmonary resuscitation for lay persons.

This history of the heart can be a somewhat “tangled” one, however. The difficulty of working on this so-important organ has occupied doctors of the Western Reserve and Cleveland Clinic for years. Want to know more about it? David S. Jones (Harvard) wrote Broken Hearts: The Tangled History of Cardiac Care to examine why it can be so difficult for physicians to determine the efficacy and safety of their treatments. Dr. Jones will be in Cleveland at the Dittrick Museum on March 21st to give the annual CMLA lecture: On the Origins of Therapies. Join us for this public talk! Register here.