Brandy L. Schillace

What was it like to be sick 50 years ago? 150 years ago?

What medical innovations most changed American lives?

How did Cleveland rise to importance as a medical city?

In other words:

How did we get here?

The Dittrick Medical History Center and Museum, in collaboration with design partners and funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, presents: How Medicine Became Modern, an innovative new way to explore the artifacts, people, and stories behind the great innovations of our age!

Museums nationally and internationally are reaching new audiences—while retaining and engaging present ones—through the medium of digital technology. The Philadelphia Museum of Art presented inter-actives for Treasures of Korea; the Field Museum of Chicago showcased a 3D exhibit about Tyrannosaurus bones; the British Museum of London installed 3D touch-activated Explorer Tables allowing virtual autopsy of a mummy. More locally, the Cleveland Museum of Art opened the award-winning Gallery One.

Now, the Dittrick Museum embarks on a project to make history come to life through a 10ft by 4ft interactive digital wall–a place where visitors can “handle” artifacts (rotating  and zooming), and more importantly, a place to engage with the human stories behind them. Partnering with Zenith Systems and Bluecadet, and supported by NEH’s Museums Libraries & Cultural Organizations grant, How Medicine Became Modern will go live in 2017!

and zooming), and more importantly, a place to engage with the human stories behind them. Partnering with Zenith Systems and Bluecadet, and supported by NEH’s Museums Libraries & Cultural Organizations grant, How Medicine Became Modern will go live in 2017!

Exhibit Details:

Free-standing 10ftx4ft wall in the main gallery

Free-standing 10ftx4ft wall in the main gallery- Ability to zoom, rotate, interact with artifacts

- Links to the stories behind artifacts/Access to interactive game-play

- Four lenses into medical history:

Want to hear more?

How would something like this work? Why would a museum want to take part in digital mediums? The 225th anniversary of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia Historical Medical Library (also the parent body of the Mütter Museum) asked these very questions in 2013. The answer? Museums and libraries must see new ways of engaging the public–and of building community. As I say in an essay for H-Sci-Med-Tech, History—far from being lost in the past—is by these means coming out to meet new friends. The story of medicine’s past offers something valuable to medicine’s future, a new way of interfacing between worlds that is both physical and digital, then and now. We enter the story through these public spaces, and through digital mediums, medical collections around the world are beginning to reach beyond them as well. What we see is a convergence of exhibit, interaction, and digital outreach.

A Practical Example from the Project:

The history of medicine offers much more than static displays or old tech. Each object, from a cast of Joseph Lister’s hand to a full-scale working x-ray machine, tells a tale of personal tragedy and triumph, of success and failure, of hopes and dreams.

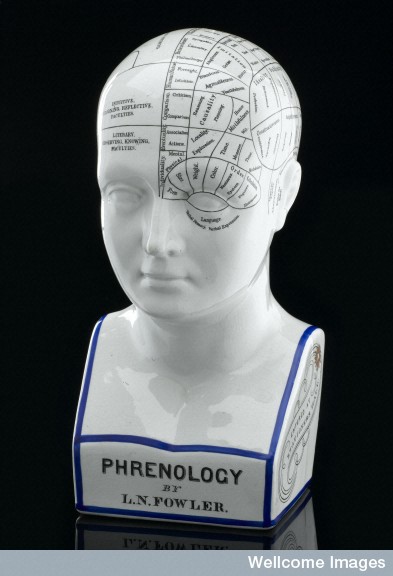

Take, for instance, the phrenology bust. Sleek, smooth–replicas are attractive enough to show up on end-tables and mantle pieces. But what’s the story? It’s about Diagnosing by the Bump!

Franz-Joseph Gall (1758-1828), proposed that different functions, such as memory, language, emotion, and ability, were situated in specific “organs” of the brain. These portions of the brain would grow or shrink with use, and the changes would appear as bumps or depressions on the skull. Called Phrenology, the practice of “reading” the bumps supposedly allowed a practitioner to assess different abilities and personality traits. Does that make sense? What might our own phrenological assessment look like? The digital display allows the viewer to see a chart with interactive sections of the brain. Why not do your own “reading”?

But that’s not the only story. Phrenology resonated with the American Dream. Johann Kaspar Spurzheim (1776-1832) arrived to begin a speaking tour, and found a very willing audience. Why? It fit the “American Dream” idea of rising from nothing, emphasizing the ability to train the mind and attain social mobility. In other words, despite the bumps you were born with, we could all get better, a kind of rags-to-riches idea very popular even today. One of Cleveland’s own doctors had his “head examined”—Jared Potter Kirtland. On the other hand, phrenology and it’s sister pseudoscience physiognomy had a dark side; they privileged one race, one class, and one sex. Not exactly a “dream” of equality. (And for the record, Kirtland did not apparently agree with the reading; the booklet has his marginal notes!) The digital display offers the visitor a window in time; they can see the images and texts (and hand written notes!) while learning about larger ethical dilemmas.

Phrenology was later abandoned and its practitioners were attacked as charlatans and fakes. Even so, phrenology helped to move psychological understanding forward in two important ways: 1. it suggested that different parts of the brain did different things and 2. It demonstrated that individual effort could be just as, if not more, important than biological inheritance. The take-away? Through digital means, the visitor doesn’t just see the bust in a cabinet. Instead, he or she can look at it closely, from all angles, and then walk through time.

Better yet, the visitor can walk through the body—through anatomies and flip books of fugitive sheets (where each layer reveals more of the anatomy underneath). So much of our fragile history remains out of reach for visitors–but digital humanities/history projects can do much more than show the item itself. It can open up that artifact as a window into another time, another place.

We look forward with great anticipation to bringing this digital history/digital humanities project to life–the human story behind medical history: “How Medicine Became Modern.”

ABOUT THE BLOGGER

Brandy Schillace, PhD, works as Research Associate and Public Engagement Fellow for Dittrick Museum. She is also a freelance fiction and non-fiction writer, lecturer, blogger, and the managing editor of a medical anthropology journal, Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. View her recent TEDx talk on the history of medicine and “steampunk,” featuring artifacts from the museum!