Who Assassinated the President?

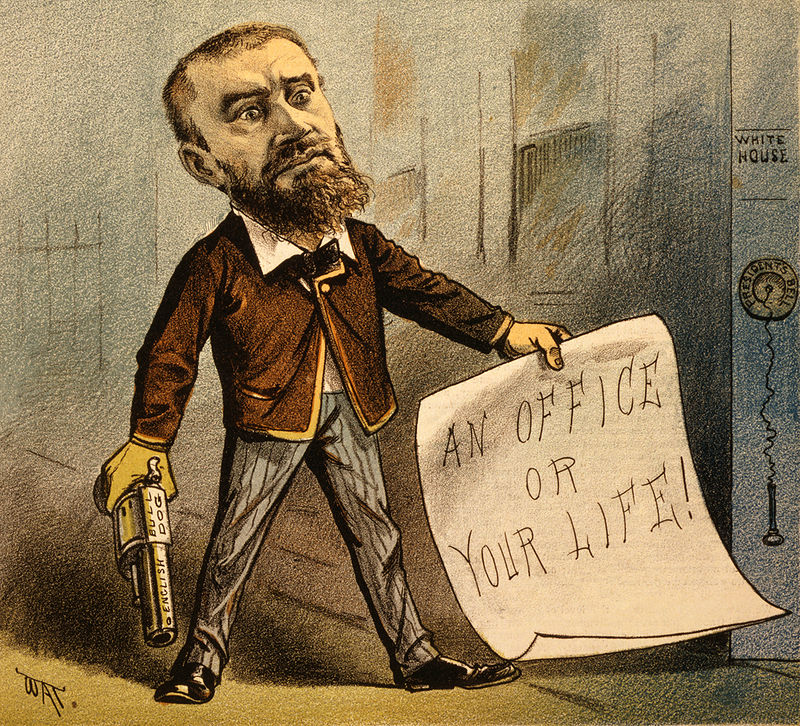

When Charles Guiteau bought an ivory-handled British Bull Dog Revolver, he was thinking of which weapon was going to look best in a museum. Because his was a mission inspired by God; he was to kill the president.

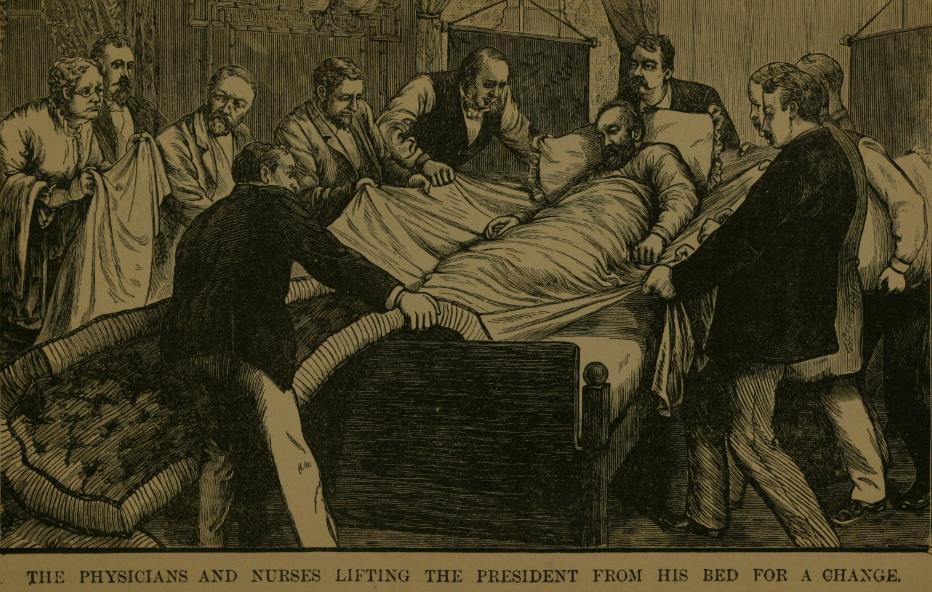

On July 2nd, 1881, after weeks of stalking him, Guiteau shot President Garfield at a public train station. The bullet from his revolver entered the president’s back, leaving shattered vertebra in its wake before becoming lodged somewhere behind his pancreas [1].

Medical historians have since determined it was the probing of his wound with dirty hands and unclean instruments by Garfield’s many physicians which lead to his septicemia and inevitable death on September 19th [2]. In fact, at his trial, Guiteau mentioned that while he acted as shooter, it was “the doctors [who] finished the work” [3, p. 138]. The aftermath of President Garfield’s passing made better antiseptic techniques a surgical necessity.

However, medical history was made on both sides of the assassin’s gun.

The trial of Guiteau, which began November 7th, 1881, was the first high profile case in the United States where a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity was ever considered. At this point in history, the physicians called upon to define insanity did so from a variety of perspectives [4].

Insanity: Evidence or Opinion?

For the defense, expert witnesses pointed to Guiteau’s “lopsided smile” and “congenital evidence of insanity” such as the abnormal shape of his skull and a “defect in his speech” [3, p. 203]. While some of the physicians working with the prosecution agreed that skull shape could indicate insanity, they found no such evidence in the defendant. Other physicians considered insanity to be a disease caused by “cerebral lesions”—but denied that Guiteau could have been experiencing such lesions as he had displayed far too much rationality.

While the prosecution’s witnesses believed that Guiteau was likely a “depraved” or “eccentric” man, they claimed he had been in possession of his faculties on July 2nd, and thus was guilty of murder [3]. They also determined that his erratic behavior in court was an act meant to support his insanity plea.

While the prosecution’s witnesses believed that Guiteau was likely a “depraved” or “eccentric” man, they claimed he had been in possession of his faculties on July 2nd, and thus was guilty of murder [3]. They also determined that his erratic behavior in court was an act meant to support his insanity plea.

While the doctors argued whether insanity was an inborn or contracted condition, and what the role of delusion was, the determination of guilt remained the jury’s. For months they watched the man who had killed their president compare himself to St. Paul and sign autographs in the courtroom [5].

Thus, despite Guiteau’s continued planning of a lecture tour and a run for the presidency in 1884, he was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death by hanging [3]. Dr. Walter Channing summed up the public’s general opinion: Guiteau was “crazy, perhaps, but not so crazy that he should not be hung.” For, while the depths of sympathy were great for the president and his family, there was “little feeling for the doer of the foul deed.” [4, p. 3]

In such a scenario, is medical evidence truly considered or simply used to alleviate a nation’s need for retribution? I leave you with the words of Channing on the subject:

The verdict shows how uncertain the boundaries are to the disease called insanity. In a case where the symptoms are at all obscure, we can almost make ourselves believe anything that we choose to. [4, p. 4]

About the Author

Catherine Osborn, BA, BS, is a graduate student in Medical Anthropology at Case Western Reserve University, the Editorial Associate at Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, as well as a Research Assistant at the Dittrick Museum of Medical History.

References

[1] Reyburn, Robert. 1894. Clinical History of the Case of President James Abram Garfield. Chicago. Journal of the American Medical Association. p. 100.

[2] Doyle, Burton T. and Homer H. Swaney. 1881. Lives of James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. Washington, D.C.: Rufus H. Darby, Printer and Publisher.

[3] Hayes, Henry G., Charles J. Hayes, Anne J. D. G. Dunmire, and Edmund A. Bailey (1882). A Complete History of the Life and Trial of Charles Julius Guiteau, Assassin of President Garfield. Philadelphia, PA: Hubbard Bros.

[4] Channing, Walter. 1882. The Mental Status of Guiteau, the Assassin of President Garfield. Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press.

[5] Guiteau, Charles. 1882. The Truth and the Removal.